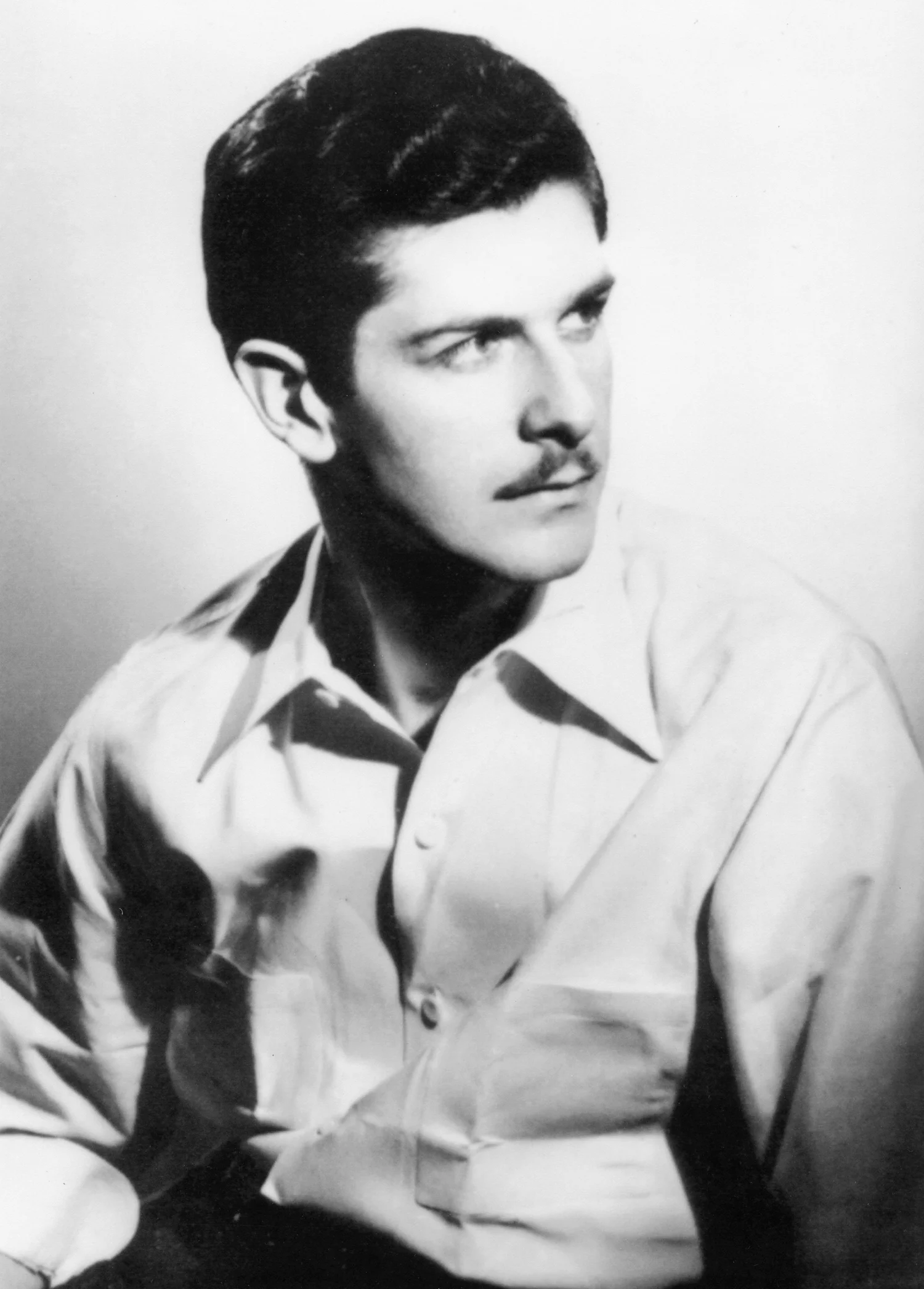

Photograph by Rochester Studio

Mennin thought a great deal about aesthetic issues, and his prominent position gave him ample opportunity to voice his views on musical composition and on the artistic life. His beliefs were remarkably consistent with each other, with the personality that emerges from his music, and with the principles he implemented at Juilliard, and he expressed himself verbally on these matters with the same kind of unequivocal confidence and sobriety that one finds in his music.

Excerpts from Peter Mennin’s Speeches and Writings

To know and understand the masterpieces of music, dance literature and the visual arts is to be liberated from the fears and lack of understanding that separate civilization from civilization, nation from nation, and man from fellow man.

Time takes its toll on works that are fashionable or routine. After a generation or two, one no longer cares whether at its creation a work was avant-garde, conservatives or middle of the road. The only criterion is that it continue to have meaning because of the quality of its artistic statement.

I would like to think that the reason anybody writes is to express something that comes from within and he will have no peace with himself until he has written the work and gotten it out of his system. Whatever it is, once said, once on paper, it is yours, not especially to share, not especially to please, it is just there and the great thing is the choice of liking it or not is one for the ages.

The composer’s relationship to the public cannot be achieved through short cuts of concessions of taste to the majority or minority, but through his desire to share the musical experiences in which he has deep conviction. There is room for dissimilar or contradictory styles…as long as the music has made a commitment of quality.

A composer can only express that which he understands; whether the soil from which he has grown is cultivated or crude does not matter. He can write worthwhile music if he clearly expresses that which is about him, using words he knows.

The arts continually recreate themselves by returning to the deep and basic values of human existence, of first principles and cannot be made to conform to any pre-conceived system – either artistic, political or social. The basic pre-condition of great art is the need of unhampered freedom to function.’ The real artist is a conduit for truth and lucidity and truth inspires humility and dedication in ones work.

In the act of performance or in the creation of new works, it is a matter of choice, not between what is right or wrong, but between what is strong and what is weak, what is lasting and what is of momentary attraction, what is truly beautiful and what is merely entertaining. These are choices all performing and creative artists must make. The QUALITY of these choices finally add up to your total stature.

In recent years I have become increasingly reluctant in making analyses of my works for use in program notes. In a sense, I feel that it is inappropriate for the composer – who has been looking inwardly during the creation of the work – to have to explain merely the compositional techniques without the emotional involvement of the content of musical ideas that created the urgency to make the work come into being. It is difficult in the extreme for the composer to analyze his work dispassionately – or should be.